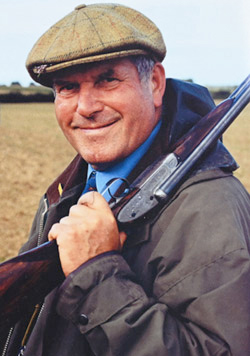

John Humphreys

Born in 1939, the distinguished sporting and countryside author John Humphreys wrote for Shooting Times for more than 40 years – for much of that time contributing the weekly ‘Country Gun’ column – until his untimely death in 2012 after a short battle with cancer. Eric Ennion was one of his early heroes and in June 1990 John wrote this piece for an issue of Shooting Times that focused on sporting and wildlife art. Reminiscing about Monks’ House some years later, he also recalled that on a bookshelf he spied Eric’s shooting diaries but, to his lasting regret, never took them down to read.

The Man Behind a Picture

One of my favourite pictures is by the late Dr Eric Ennion. I bought it for a tenner, many years ago at some long-forgotten Game Fair, and it depicts

a fox in the sand dunes in the act of pouncing on a black-headed gull. The picture is the original of one of the plates in the book Tracks, which

Dr Ennion compiled with Niko Tinbergen. By any standards I had snapped up a bargain

In my formative years I was a disciple of Ennion. I sat at the feet of the great man, admired him immensely and enjoyed some happy times in his

company. I was a raw youth who had been little further from home than Cambridge when my mother spotted an ad in that international publishing

giant The Nursery World. A bird observatory in Northumberland offered holidays for members of the faith and, knowing my interest in the fowls

of the air, I was put on the train at Ely station bound (after two changes) for Morpeth, whence I was to take the bus to Seahouses and then walk

the mile or so along the coast road to Monks’ House Bird Observatory. My mother thought that she might never see me again – me being unfamiliar

with trains, and all.

To the surprise of all I arrived safely and went to bed with the flashing light of the lighthouse on Inner Farne pulsing across the curtains. For

many years thereafter I was to make that journey north and spend a fortnight at Monks’ House chasing and ringing birds. A wildfowler manque I

certainly was but I learned discretion quickly; the other residents at Monks’ House were birdwatchers, full stop, so when a skein of Greylags flew

over at 20 yards I held my tongue and even controlled myself sufficiently not to swing an imaginary gun at them and bring a couple crashing down.

We spent long, lazy days lurking in the dunes with our plover net out on the wrack as the tide flowed. Before it on the sand ran waders, dunlin,

sanderling, ringed plover, curlew, oystercatcher, godwit and so on. It was almost as good as punt-gunning, for when the birds ran into your catching

area you gave a great heave on your clothes line, the net flicked over and you might have half-a-dozen birds bouncing under the trammels.

Sometimes the net was bogged down by sand and weed and it failed to spring over; at others the birds had run across and you had gone to all that

trouble for a blank, for the net had to be moved further up the beach and laboriously re-set. When we made a bag, the birds were carefully identified,

ringed and released.

My special contribution was the invention of an eider duck trap. These curious fowl would come and dibble in a freshet which ran down the beach and

spread out as it reached the sea. In eclipse and flightless, still they were impossible to catch. I devised a dodge whereby a sort of tennis net

with a post at each end was lain flat across this stream way down on the beach. As the tide made and the duck paddled across it, we heaved

simultaneously on two ropes, the net sprang upright and the duck were prevented from getting back to sea and safety. It called for some nifty

sprinting, but we caught several.

Once a week Dr Ennion took us out to the Farne Islands on the fishing cobble Glad Tidings. There we would ring the immature lesser black-backed gulls,

shags which we lassoed off their nests and puffins which we bagged with a sort of miniature shepherd’s crook. Lunch we would eat on the sun-backed,

white-splashed rocks while rabbits scuttled in the sea lavender, kittiwakes screamed and Glad Tidings, at her mooring, tilted and swung. Another treat

was the trip to the Bass Rock for the gannets or to nearby Holy Island, Lindisfarne of St Cuthbert and home of mighty punt-gunners, fowlers and

favourite stamping ground of Ralph Payne-Gallwey. Here we set mist nets across the ‘Lonnens’ and beat the bushes to see what migrants flew into

them.

To extricate birds from a mist net takes patience and skill and a family of long-tailed tits would test all but the most phlegmatic. This delicate

job we left to the ladies who were always better at it than clumsy men who tended to grow impatient. Our most spectacular catches were a bluethroat,

a sparrowhawk which did not care one bit for the experience, a bullock and a postman complete with bicycle.

Eric Ennion, with his weather-beaten face and patriarchal fringe of snowy hair, his patience and indefatigable kindness, was ever present, organising,

advising, gently prompting, impervious to cold. On the famous day when we caught and ringed the first Temminck’s stint he was sloshing about in black

plimsoles in sewage farm ooze, regardless of the sciatica to which he was a martyr. I never saw him with a coat and the rain fell on him unhindered,

but that sunny countenance seemed to warm the chilly drops as they ran down his cheeks. The ornithologist James Fisher was there that day and there

was great celebrating.

In the 1920’s and 30’s Eric Ennion was a Cambridgeshire GP and a keen shooting fenman. His classic book (I use the word deliberately), Adventurers

Fen, is a unique record of the prewar fenland and in those days Eric was a great shooting man. It was said that he would attend a confinement with

a pair of rabbit’s ears or a cock pheasant’s tail showing at the tail of his battered tweed jacket.

At the end of the war he gave up medicine to open the Flatford Mill Field Centre for the Field Studies Council, moving later to Monks’ House. In 1961

he retired to Wiltshire where he concentrated on further studies of birds and painting and sketching them.

His chunky style is unmistakable, and he was completely self-taught, having painted and drawn, as he put it, “since I came out of the egg”. His work

puts an emphasis on economy of line and colour but shows a mastery of movement. He was especially good at depicting duck, waders and other waterbirds

and the reflections, shadows and patterns of water which surround them.

So, I have on my wall a painting only a glance at which brings back a flood of memories and a clear picture of the great man up to his knees in mud,

chuckling that Santa Claus chuckle (I hear it now), his cornflower-blue eyes full of fun and joy, cupping in his great hands a dainty little wader.

In our hands birds would fret and struggle, but in his they lay quiescent and trusting. Such a picture is worth ten times more than something bought

just as a soulless investment. Your sporting pictures should be of places you like, of subjects you like and by people you like.

Dr Ennion forsook the gun for the binoculars and paintbrush; it is a not unfamiliar metamorphosis and who knows but one day we too…? However, it

came as a relief to me to discover on a chance visit to his study far away and long ago at Monks’ House, a double-barrelled 16-bore and a packet

of cartridges lying on the table near his desk. Old habits die hard and once the sport is in the blood…

© The Estate of John Humphreys / Shooting Times 1990

Artwork © The Estate of E A R Ennion / Oxford University Press 1967