Flatford Mill

At the end of the war Eric Ennion sold his Cambridgeshire medical practice and bought Hay Barn Cottage on the hill above Flatford Mill in Suffolk,

intending to earn his living as an artist and freelance writer and broadcaster. Instead, he became the first warden of the pioneer Field Centre at

Flatford, moving with his family from Burwell to the Mill House – the building on the right in the photograph.

For the next five years he ran courses on birds, insects, plants, freshwater and estuarine biology, and landscape painting – in fact on almost any

subject connected with the countryside. He was joined by an entomologist, John Sankey, and later by a botanist, Jim Bingley. They deliberately took

courses in each other's specialities to broaden their knowledge.

Birds were Eric's first love of course, and for the 1948 season he doubled the number of special bird courses to six. They were aimed at independent

students – the “serious beginner” and the “seasoned amateur” – and he needed to spread the word. Although the RSPB had only a few thousand members

in the late 1940's, its magazine Bird Notes certainly reached part of the target audience; the following article appeared in the 1947-48 winter

issue.

In those days there was no barrage at Cattawade and the tide flowed unhindered as far as Flatford. Eric did the line drawing of Flatford Mill for The

New Naturalist – A Journal of British Natural History, in 1949.

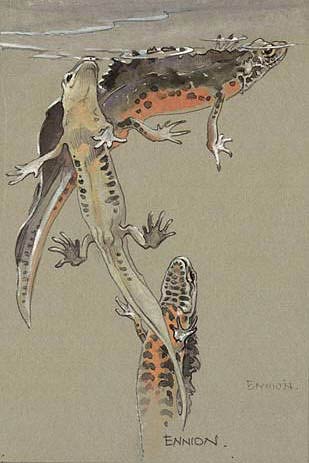

Crested Newts

205 x 135 mm

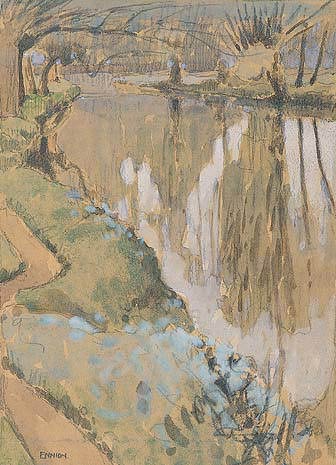

The River Stour above

Flatford Mill

185 x 135 mm

Walberswick Marshes

Oct 20 '47 – Sea Aster

blowing by the ditches

255 x 360 mm

Bird Weeks at Flatford

By E A R Ennion, Warden

Flatford Mill is one of four Field Centres established by The Council for the Promotion of Field Studies for the serious study of countryside

activities, natural history and art. With close upon fourteen hundred students coming and going during the past two seasons, it is the first ever of

its kind to take resident visitors on a large scale and on a really comprehensive basis, for every outdoor subject may be studied at first hand. The

Mill buildings are leased from the National Trust; the adjoining Valley Farm from the Ancient Buildings Trust; and the Carnegie Trust generously

defrayed most of the initial establishment costs.

Flatford Mill begins its third season with a Bird Course on December 29th. The three other Centres which will open next spring are Juniper Hall,

Box Hill, Surrey; Malham Tarn, on the Craven Pennines in Yorkshire; and Dale Fort, Pembrokeshire; this last in conjunction with the West Wales Field

Society, whose earlier work at the island observatory on Skokholm will be known to most bird observers.

There are, of course, no shearwaters at Flatford. Instead, the estuaries of the Stour and the Orwell and the network of creeks and saltings around

Horsey Island – a vast and teeming expanse of mudflats at low tide – the river upstream of the Mill, the surrounding lanes and woods and fields,

offer a far greater, if less spectacular, variety of birds – although, to be sure, it is not everywhere that one finds wigeon and brent, shelduck

and curlew in due season, and even flocks of black-tailed godwits several hundreds strong at one's back door! Herons, kingfishers, common and green

sandpipers, grey, yellow and pied wagtails, the three woodpeckers and all the summer warblers occur more immediately around the Mill: nightingales,

blackcaps and garden warblers were singing almost side by side last spring in the Valley Farm garden.

The value of Field Centres lies not only – or even chiefly – in the wealth of wild-life and countryside activity all round. These might be found in

scores of other places if one knew what to look for and had eyes that were trained to see. And this is the first care of a Field Centre, with its

expert staff, its special equipment and its fund of local knowledge: to show you where and how to look and what to look for; how to sort and marshal

and record the gist of what you've seen: to teach the rudiments of fieldcraft and technique; to lay the foundation of scientific method. For that is

the key to knowing your countryside. It is not true to say that enquiry hinders enjoyment; that is a lazy way of evading the issue. It is certainly

possible to get great pleasure and content from the countryside without much more than superficial knowledge of its structure or of its creatures and

their ways. But to the true naturalist, or artist, deeper understanding can only deepen wonder and respect. This is perhaps especially true of the

birdwatcher.

Field Centres are not merely for pleasure, like holiday camps, or pieds à terre in pleasant country, like youth hostels. Nor are they primarily

research stations, like Plymouth or Wray Castle, for the more advanced biologist. There is provision – and ample provision – for the expert,

professional or amateur (the distinction is one of status rather than of knowledge) and for anyone wishing to do research, to write or to paint

a picture. There is every provision, too, for groups from universities, training colleges and schools. But Field Centres are perhaps of greatest

value for the serious beginner and for what might be called the "seasoned amateur", for whom hitherto precious little has ever been done. Now,

independent students of outdoor subjects may safely be said to have come into their own. No less than a third of the nine hundred residents who

came to Flatford Mill during 1947 were independent students and many of them came to study birds.

Three special Bird Courses were held, one in the spring, one in the autumn, and one at midsummer with the avowed task of trying to discover why, at

a time when the bird population must be at its highest, so little of them is actually seen and heard. The problem remains largely unsolved, but

sufficient was gleaned to establish that there is a problem, and a very fascinating one, which will be a focus of future enquiry. The spring course

was particularly concerned with distribution, territory and song; the autumn course with flocking, autumn migration and feeding habits on the

estuary. Both included studies of flight, roosting, general behaviour and identification. There are six Bird Courses planned for 1948, each lasting

a week and limited to thirty students.

The party assembling for a course is mixed in every way – in age and sex, in background and approach, in knowledge and in experience – the only

common factor (and the only one that matters) is a genuine interest in birds. The scheme for the course, already outlined roughly by the Warden,

begins to take its final shape when he meets and is able to assess his personnel. Teams are chosen and the plans explained, although last-minute

changes will often be prompted by the weather. The scheme includes a number of short informal lecture-demonstrations – on flight or pellets or

adaptive coloration, for example – and a number of "briefings" before the various day or night excursions are undertaken. But, except in hopelessly

bad weather, as little time as possible is spent indoors. Also, the time spent in lecturing, in instructing and in pointing things out on walks in

the ordinarily accepted way is reduced to a minimum: telling people what to do, how to take notes and make use of cover, and showing them how to do

things for themselves and how to interest other people, are far more vital matters.

Something you find out for yourself – a trick of flight, a note, a feeding habit or some small identification point – will always be remembered.

It is worth a dozen similar hints picked up secondhand at a lecture. So, rather than tell you, we try to inveigle you into making your own

discoveries. And, once you have learned the way to look, it is amazing how much you notice that you had never seen before about the birds you

thought you knew so well that there was nothing left to look for. Birdwatching then becomes an all-absorbing day-by-day experience. It no longer

needs the continuous stimulus of chasing rarities; still less the selfish scientifically indefensible side-line of egg-collecting. You are beginning

to become a real naturalist.

The fields and lanes; the gardens and orchards; the overgrown hedgerows, thickets, spinneys, and the woods themselves; the riverside marshes and

willow holts; the tidal flats and saltings of the estuary, all come into the picture when studying birds. Counts, recording observations of their

singing, feeding, breeding and roosting habits and times; making maps of woods or other cover and plotting on them territories, nesting sites and

song posts; comparing woodland and other types of habitats; investigation of flight and food and broods; a certain amount of anatomy and physiology –

such details, for example, of feather and wing structure as are essential preliminaries to studying flight outdoors – all these, too, form, as it

were, the background against which one puts the immediate problems of fieldcraft, method and identification. Later on, when it is possible to equip

and secure a site nearer the coast, a trapping and ringing station will be set up.

There is another, more remote, but vitally important background: the Centre itself, with its library (specially well stocked for birds) and study

collections; its laboratories and general living rooms. There are always other people working there – botanists, entomologists, geographers,

historians, landscape artists. Thus it is nearly always possible to get an opinion on some outside point, and the Warden and his Assistant Warden,

both expert field naturalists, are always ready to help and advise. This mingling of interests that Field Centres encourage, goes far towards breaking

down those false, but almost inevitable barriers which any one department of science tends to establish against the others.

There are no such barriers in nature. Each facet – and these will include tide and weather, river and hill and soil as well as animal and plant –

dovetails with the next. If there is a divide it falls between things living and things dead: between the live plant or bird or insect, and the

specimens in the drawer or in the bottle on the laboratory shelf. For too long the teaching of biology has relied upon things dead eked out with

stodgy textbooks, bench experiments, and the inmates of aquaria and breeding cages. At Flatford the countryside provides the setting and a

creature's normal habits of living control the experiment. That would seem to be the sensible way to study Life.

Photograph of Flatford Mill © Photochrom Co Ltd

Text and all other images © The Estate of E A R Ennion

Introductory text © Bob Walthew